In the media: As buildings reopen, stagnant water may harbor unseen risks

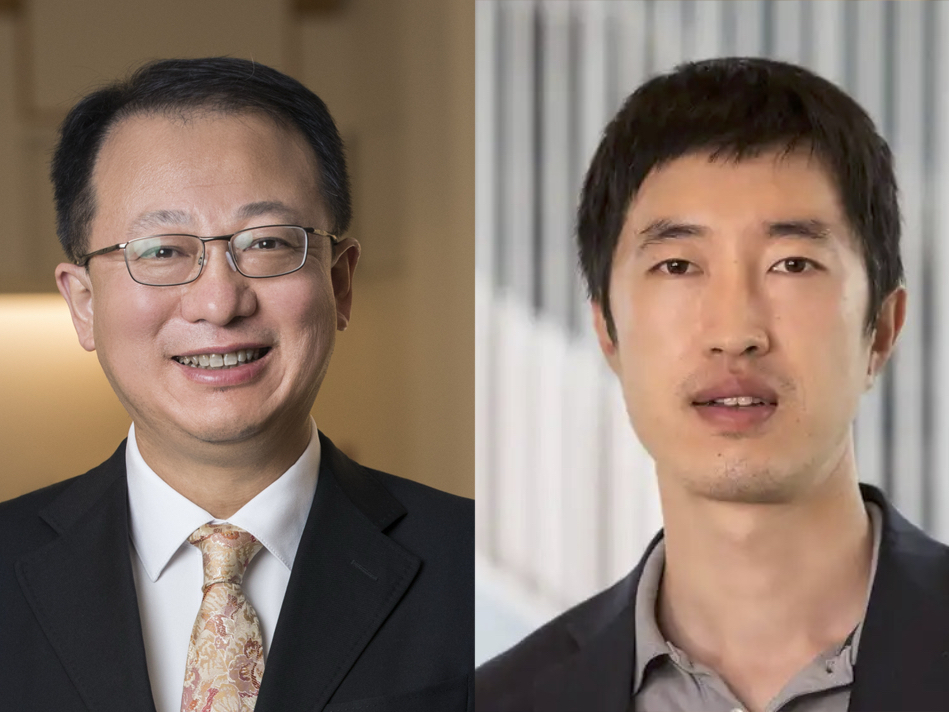

Assistant Professor Fangqiong Ling discusses the risks of bacteria in stagnant water

After sitting empty for months, offices and commercial buildings in St. Louis are beginning to reopen — many with freshly installed Plexiglas barriers to protect workers from passing the coronavirus.

But researchers warn of other health risks that may be lurking in the plumbing systems of these once-shuttered buildings.

With fewer users, pipes have held stagnant water for weeks or months at a time. Some waterborne pathogens thrive in this environment, while heavy metals can slowly leach out of aging pipes. The sheer number of unoccupied buildings during the pandemic has some researchers concerned about a potential spike in waterborne illnesses.Fangqiong Ling, an assistant professor in Washington University’s McKelvey School of Engineering, has spent her career studying bacteria in stagnant water.

It’s still unclear, she said, how these complex communities will change over a period of months.

“Previously, we were thinking more about stagnation for weeks,” Ling said. “Stagnation for months is a new question.”