Model predicts economic, public health repercussions of lifting quarantine before COVID-19 vaccine

To avoid ‘worse’ outcome than past two months, model suggests seniors quarantined, measured reopening — under certain conditions

COVID-19, the disease caused by the SARS-Cov-2 virus, was officially declared a pandemic on March 11 by the World Health Organization. Nearly two months later, many municipalities and states around the country have decided to relax some of the limitations put in place to prevent the disease from spreading at a pace that threatened to overwhelm the health care system.

New interdisciplinary research from Washington University in St. Louis — carried out by an electrical and systems engineer and a biomedical engineer from the McKelvey School of Engineering and a health care economist from the Olin Business School — outlines the effects on the economy and health outcomes of three distinct quarantine scenarios.

Their model indicates that, of the scenarios they consider, keeping a strict self-quarantine policy for seniors until the number of new infections is drastically reduced, while gradually loosening the policy for the rest of the population, will lead to the best economic and health outcomes.

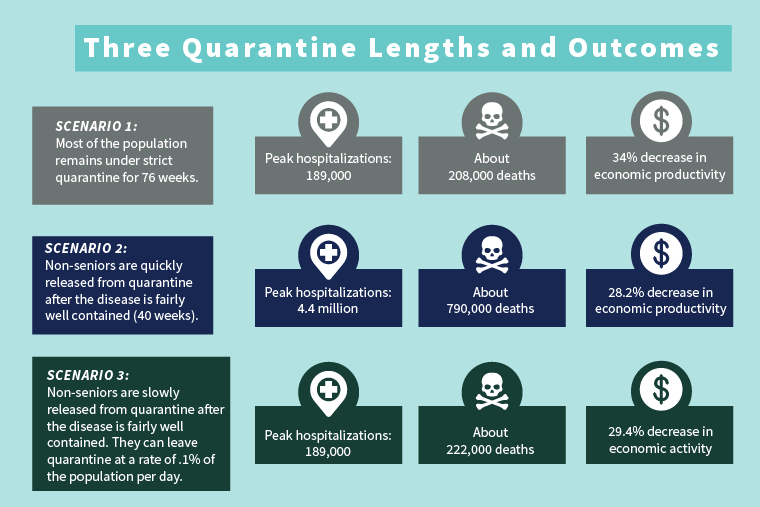

One key result is the model’s prediction of the way in which different scenarios affect the number of people hospitalized. In two scenarios, the maximum number of simultaneous hospitalizations is about 189,000. In one, however, about 4.4 million people would need to be hospitalized at once.

Their work is published on MedRxiv and is currently under review.

In general, the team sought to answer the question: “What is the most effective way to handle a country-wide quarantine for 76 weeks?” by which time the model assumes a vaccine is available. “The goal is to quantify and mitigate the impact of the current pandemic,” according to Arye Nehorai, the Eugene and Martha Lohman Professor of Electrical Engineering in the Preston M. Green Department of Electrical & Systems Engineering.

The group — which also includes David Schwartzman, a business economics PhD candidate in the Olin School, and Uri Goldsztejn, a PhD candidate in biomedical engineering — started with a Susceptible, Exposed, Infectious, Recovered (SEIR) model, a commonly used mathematical tool for predicting the spread of infections. This dynamic model allows for people to be moved between groups known as compartments, and for each compartment to in turn influence the other.

At their most basic, these models divide the population into four compartments: Those who are susceptible, exposed, infectious and recovered.

Nehorai and his team used compartments with data sourced from peer-reviewed sources:

-

Susceptible population

-

Quarantined susceptible population

-

Exposed population

-

Quarantined exposed population

-

Infected hospitalized population

-

Infected asymptomatic population

-

Quarantined infected asymptomatic population

-

Dead population

-

Recovered population

-

Quarantined recovered population

Beyond those 10 categories, each was subdivided into seniors, aged 60 and older, and non-seniors, as well as into those who are more able to work from home and those whose productivity is more damaged at home and who earn less to begin with.

“And then we added something very important,” said Goldsztejn. “A large fraction of the population is asymptomatic. These people move a lot and are contagious, as opposed to ebola, for instance, where the sick are easy to spot and isolate.”

The team’s model was able to incorporate these people, as well. They did so by varying the contagiousness of asymptomatic people to mirror public health measures and individual behavioral changes in responses to the severity of the pandemic. To account for improvements in health knowledge over time, they model better health outcomes for those getting sick later.

Rushing to reopen worse in the end

In the end, the model shows three different possibilities of how quarantine might play out in the economy and in the health care system based on three different policy responses.

What they found, in short: “Rushing to reopen public spaces and businesses is great for a few weeks, but down the line, it’s very much worse,” Goldsztejn said.

In all three scenarios, there are three constants: 85% of non-seniors are quarantined; no restrictions are loosened for the first 40 weeks; a vaccine is available in 76 weeks; the majority of seniors remain quarantined until the vaccine is available.

In the first scenario, fairly restrictive quarantine measures are kept in place for 76 weeks. That leads to a sharp economic decline and about 200,000 deaths.

In the second, restrictive quarantine measures remain for 40 weeks, at which point the non-seniors go back to business as usual. This would lead to a rapid economic recovery followed by a second outbreak. Strict quarantine measures would need to be reestablished, which would undo any economic gain, and result in about 700,000 deaths.

The third scenario is similar to the second, but instead of going straight back to business as usual, the non-senior population leaves quarantine at a rate of 0.1% per day. Modeling shows this scenario to foster slow, steady economic improvement and about 220,000 deaths — with no second outbreak.

The addition of asymptomatic people had a profound effect, as well, suggesting that public health measures aimed at everyone — such as social distancing and limiting gatherings — will also help to limit the spread of the disease.

The scenarios considered by the model shared one outcome: No quarantine approach could bring economic and health outcomes back to pre-pandemic stages before a vaccine becomes available.

“Our research on modeling COVID-19 spread and the economy shows that it is critical to open the markets gradually while continuing the quarantine of seniors,” Nehorai said. In real-world terms, this means lifting restrictions at work several industries at a time, or gradually letting more low-risk people gather in one place.

However, he said, “If policymakers prioritize short-term economic productivity more, their quarantine policies may lead to many times more deaths and hospitalizations with minimal short-term economic gain.”