New research finds 1M deaths in 2017 attributable to fossil fuel combustion

Comprehensive evaluation of source sector, fuel contributions to the PM2.5 disease burden analyzed across over 200 countries

An interdisciplinary group of researchers from across the globe has comprehensively examined the sources and health effects of air pollution — not just on a global scale, but also individually for more than 200 countries.

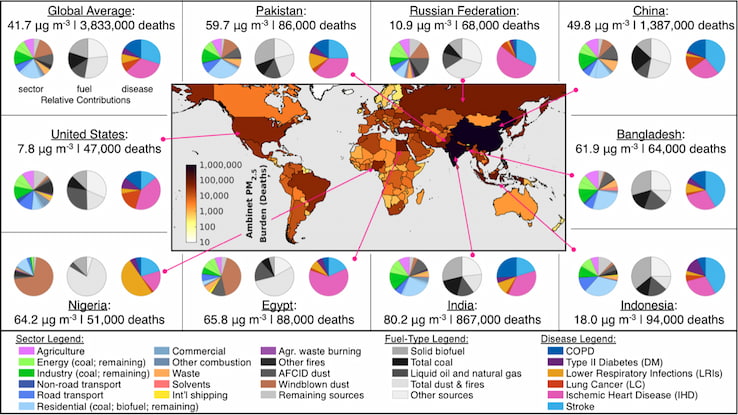

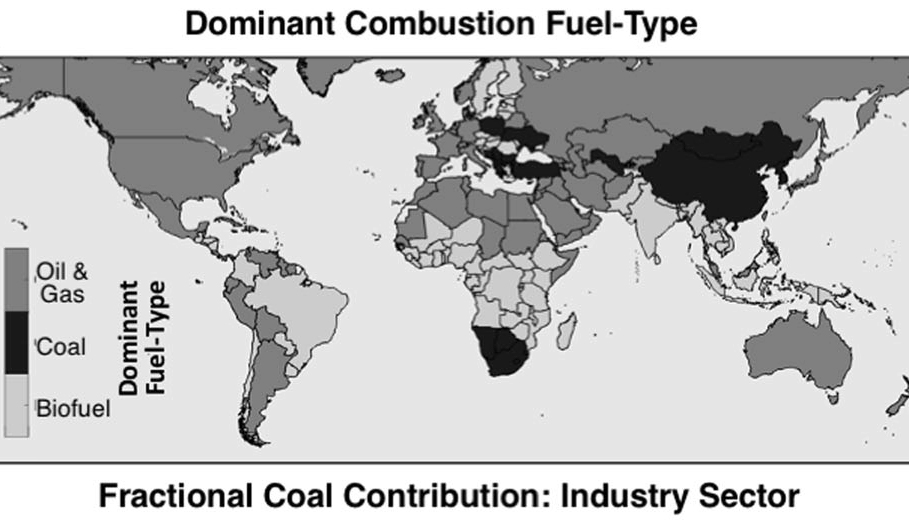

They found that worldwide, more than one million deaths were attributable to the burning of fossil fuels in 2017. More than half of those deaths were attributable to coal.

Findings and access to their data, which have been made public, were published today in the journal Nature Communications.

Pollution is at once a global crisis and a devastatingly personal problem. It is analyzed by satellites, but PM2.5 — tiny particles that can infiltrate a person’s lungs — can also sicken a person who cooks dinner nightly on a cookstove.

“PM2.5 is the world’s leading environmental risk factor for mortality. Our key objective is to understand its sources,” said Randall Martin, the Raymond R. Tucker Distinguished Professor in the Department of Energy, Environmental & Chemical Engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis.

Martin jointly led the study with Michael Brauer, a professor of public health at the University of British Columbia. They worked with specific datasets and tools from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, the Joint Global Change Research Institute at the University of Maryland and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, as well as other researchers from universities and organizations across the world, amassing a wealth of data, analytical tools and brainpower.

First author Erin McDuffie, a visiting research associate in Martin’s lab, used various computational tools to weave the data together, while also enhancing them. She developed a new global dataset of air pollution emissions, making it the most comprehensive dataset of emissions at the time. McDuffie also brought advances to the GEOS-Chem model, an advanced computational tool used in the Martin lab to model specific aspects of atmospheric chemistry.

With this combination of emissions and modeling, the team was able to tease out different sources of air pollution — everything from energy production to the burning of oil and gas to dust storms.

This study also used new remote sensing techniques from satellites in order to assess PM2.5 exposure across the globe. The team then incorporated information about the relationship between PM2.5 and health outcomes from the Global Burden of Disease with these exposure estimates to determine the relationships between health and each of the more than 20 distinct pollution sources.

As McDuffie put it: “How many deaths are attributable to exposure to air pollution from specific sources?”

Ultimately, the data reinforced much of what researchers already suspected, particularly on a global scale. It did offer, however, quantitative information in different parts of the world, teasing out which sources are to blame for severe pollution in different areas.

Ultimately, the data reinforced much of what researchers already suspected, particularly on a global scale. It did offer, however, quantitative information in different parts of the world, teasing out which sources are to blame for severe pollution in different areas.

For instance, cookstoves and home heating are still responsible for the release of particulate matter in many regions throughout Asia, and energy generation remains a large polluter on the global scale, McDuffie said.

And natural sources play a role, as well. In West sub-Saharan Africa in 2017, for instance, windblown dust accounted for nearly three quarters of the particulate matter in the atmosphere, compared with the global rate of just 16 percent. The comparisons in this study are important when it comes to considering mitigation.

“Ultimately, it will be important to consider sources at the subnational scale when developing mitigation strategies for reducing air pollution,” McDuffie said.

Martin and McDuffie agreed that, while a takeaway from this work is, simply put, air pollution continues to sicken and kill people, the project also has positive implications.

Although pollution monitoring has been increasing, there are still many areas that do not have the capability. Those that do may not have the tools needed to determine, for instance, how much pollution is a product of local traffic, versus agricultural practices, versus wildfires.

“The good news is that we may be providing some of the first information that these places have about their major sources of pollution,” McDuffie said. They may otherwise not have this information readily available to them. “This provides them with a start.”

The McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis promotes independent inquiry and education with an emphasis on scientific excellence, innovation and collaboration without boundaries. McKelvey Engineering has top-ranked research and graduate programs across departments, particularly in biomedical engineering, environmental engineering and computing, and has one of the most selective undergraduate programs in the country. With 140 full-time faculty, 1,387 undergraduate students, 1,448 graduate students and 21,000 living alumni, we are working to solve some of society’s greatest challenges; to prepare students to become leaders and innovate throughout their careers; and to be a catalyst of economic development for the St. Louis region and beyond.

This research was supported by the Health Effects Institute (HEI), an organization jointly funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA; Assistance Award No. R-82811201) and certain motor vehicle engine manufacturers.