New system creates bioplastics, consumes CO2

Method could reduce nondegradable plastics and greenhouse gas emissions

A team of researchers has developed a system that uses carbon dioxide, CO2, to produce biodegradable plastics, or bioplastics, that could replace the nondegradable plastics used today. The research addresses two challenges: the accumulation of nondegradable plastics and the remediation of greenhouse gas emissions.

The work was published in the Sept. 28 edition of the journal Chem.

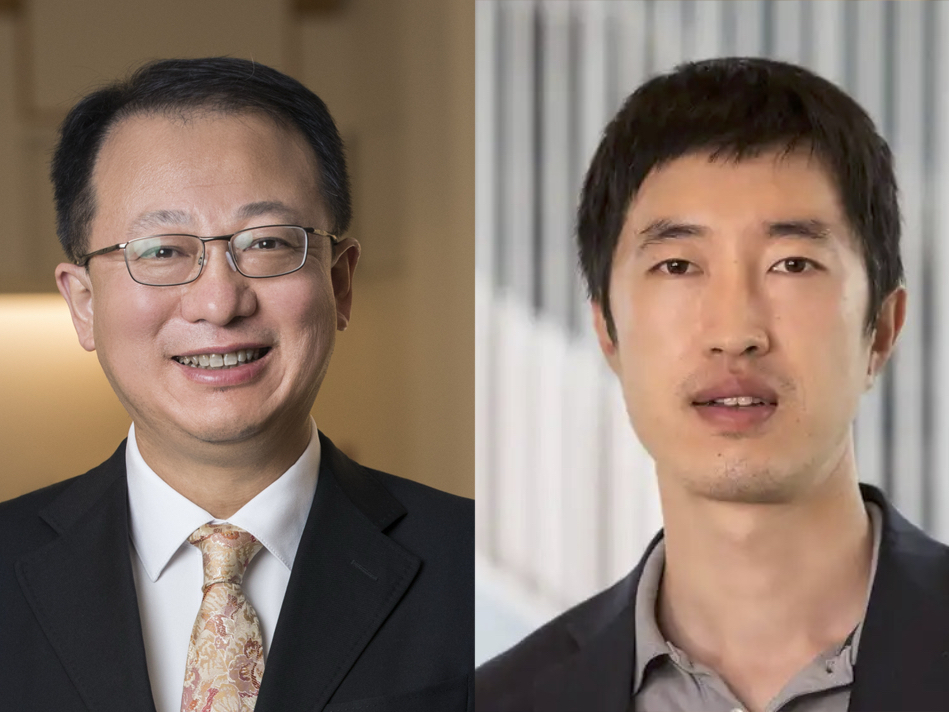

The research was a collaboration of Texas A&M AgriLife researcher Susie Dai, associate professor in the Texas A&M University Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, and Joshua Yuan, the Lucy & Stanley Lopata Professor and chair of energy, environmental and chemical engineering at Washington University in St. Louis’ McKelvey School of Engineering. Yuan was formerly with the Texas A&M Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology.

The researchers and their laboratory scientists worked for almost two years to develop an integrated system that uses CO2 as a feedstock for bacteria to grow in a nutrient chamber solution and produce bioplastics.

“The technology’s benefits are multifaceted,” Yuan said. “It is carbon negative and can certainly mitigate global climate change while at the same time producing degradable plastics that can replace nondegradable petrochemical plastics.”

The team’s platform also has a much faster reaction rate than photosynthesis, which also captures CO2, and has a higher energy efficiency. And if the technology is successful enough to produce bioplastics at an economic scale, industries could replace traditional plastic products with ones that have fewer negative environmental impacts. In addition, mitigating CO2 emissions from energy sectors such as gas and electric facilities would also be a benefit.

“The key was to convert CO2 to something that microbes can use,” Yuan said. “We choose acetate and ethanol as the intermediates. These water-soluble molecules enabled rapid electron, energy and mass transfer and allowed the whole system to run fast.”

Read the full story in AgriLife Today.