Interdisciplinary team harnesses mechanobiology to combat kidney disease

Guy Genin and Jeffrey Miner at WashU collaborate to uncover mechanical forces behind incurable kidney condition

Chronic kidney disease affects an estimated 37 million people in the U.S., and for many, there is no cure. But a new research project at Washington University in St. Louis seeks to change that by uncovering the mechanical basis of kidney cell injury.

To tackle chronic kidney disease, Guy Genin, the Harold and Kathleen Faught Professor of Engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering at WashU, and Jeffrey Miner, the Eduardo and Judith Slatopolsky Professor of Medicine in Nephrology at WashU Medicine, teamed up with Hani Suleiman, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The interdisciplinary team, with expertise spanning medicine, cell biology, genetics and engineering, received a five-year, $4 million grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

With the NIH’s support, the team plans to study the mechanobiology of podocytes, specialized cells in the kidney that help filter blood.

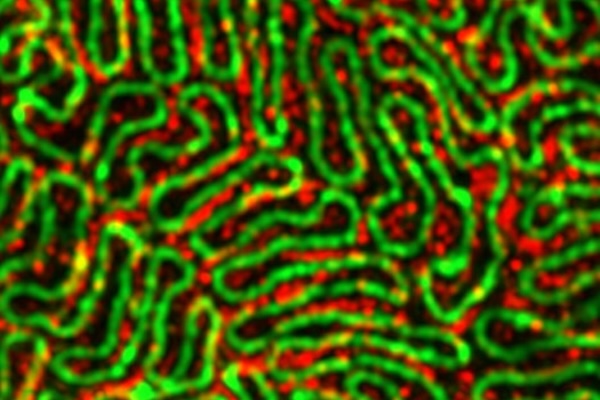

“Podocytes look a bit like octopi that are hugging their neighbors,” said Genin, who is also the co-director of the National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center for Engineering Mechanobiology (CEMB). “When you look at these tentacles with advanced microscopy, the ways that they come together to form the kidney’s filtration system become clear. Without these connections, the entire filtration system falls apart. Everyone is born with a certain number of podocytes. You lose some over time, including a few every time you go to the bathroom, but certain diseases and injuries to the kidneys can cause you to lose them much faster.”

The team aims to help people keep more podocytes for longer, delaying the onset of kidney dysfunction. They’re focused on Alport syndrome, a genetic disorder in which podocytes are injured, leading to impaired kidney function that does not heal. The team hypothesizes that injury and the potential for healing are closely associated with podocytes’ mechanobiology, or how podocytes sense and respond to mechanical forces, including forces that might disrupt podocytes’ structure and cause them to detach from the kidney's filtration barrier.

"We're excited to apply cutting-edge mechanobiology approaches to study this important disease that currently lacks targeted treatments," said Miner, an international expert on Alport syndrome. "By uncovering the mechanical basis of podocyte injury, we hope to gain insights that could lead to new therapies."

The project leverages expertise across disciplines, with Miner's lab providing knowledge of kidney biology, Suleiman bringing expertise in advanced imaging techniques and cell biology, and Genin contributing knowledge of mechanical forces in living systems. The team will use state-of-the-art imaging, including super-resolution microscopy, to visualize podocyte structure in unprecedented detail. They will also employ techniques to measure and manipulate the mechanical forces on cells.

The team says its basic science findings could lay the groundwork for translational studies to develop new therapies for Alport syndrome and potentially other kidney diseases. With new understanding of podocyte structure and advanced mechanobiology models, the team can find new techniques to help podocytes hold on, even when injured.

"As a physician-scientist, I'm motivated by the potential to move from molecular-level discoveries to real clinical impact for patients," said Suleiman. "This sort of interdisciplinary research is key to making those leaps."