David Peters: Inspired by Sputnik

In 1970, David A. Peters, PhD, faced a dilemma. He had been offered an attractive position with a U.S. Army Laboratory in Ames, Calif., to further his research on helicopters — his expertise — which was highly coveted by the Army in the midst of the Vietnam War. There was just one catch: Peters was deferred from military service because he was employed by defense contractor McDonnell Douglas Corp., and the U.S. Selective Service System had just ruled that such a deferment was one-time only and not portable. Mobility was not an option.

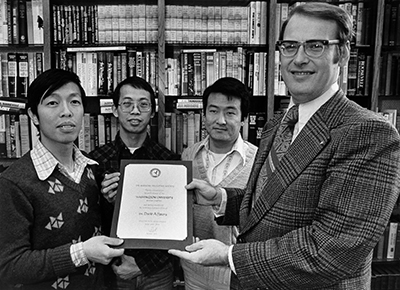

When Peters, now the McDonnell Douglas Professor of Engineering in the Department of Mechanical Engineering & Materials Science, told his potential boss, Paul Yaggi, PhD, of his dilemma, there was a long pause at the other end of the line.

“Dr. Yaggi finally said, ‘David, we ARE the U.S. Army, and we’ll get you the deferment and also send you to Stanford to get your PhD.’ I didn’t even ask what the salary was. We were on our way.”

Peters and his wife left for California and came back to St. Louis and Washington University in 1975, with children Michael and Laura in hand (son Nathan was later born in St. Louis). In 1974, at the urging of then Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering chair Salvatore Sutera, PhD, Peters interviewed for a faculty position at Wash U, but turned down a job offer. A year later, he and his wife discussed the decision one morning and concluded that they’d made a mistake. Later that same day, Peters received a letter from Sutera, who once again offered him the position.

“I was meant to be a professor and just didn’t know it. I owe my career to Sal Sutera.”

— David Peters, PhD

“I was overjoyed,” Peters says. “We came back and never regretted it.”

Sutera is now senior professor and was dean of the School of Engineering & Applied Science from 2008-2010.

Peters was born in East St. Louis, Ill., and grew up near Fairview Heights. A product of the space race era, he was motivated at age 10 by a little Russian satellite.

“We’d go out in the back yard and watch Sputnik go over,” Peters recalls. “It was such a shock that the Russians had this and we didn’t. I’d thought that America was the greatest country in the world, and all of a sudden we’re not. That was when I decided to be a space engineer.”

He was admitted to Washington University in 1965 with a full scholarship from Procter & Gamble.

Sutera encouraged Peters to pursue his master’s even before he had finished his undergraduate career. His introduction to helicopters came through legendary helicopter pioneer Kurt Hohenemser, co-producer of the first operational helicopter, then a researcher at McDonnell Douglas and adjunct WU faculty member, who became his adviser.

For more than four decades, Peters and his group have made globally recognized contributions to helicopter research, especially in the realm of mathematical models of helicopters. The algorithms he has developed are cornerstones of helicopter design: His mathematical models can predict the real-time response of a helicopter to a wide range of flight conditions and can be put into a flight simulator for pilot training. He is especially interested in models of how the air is being pumped.

A current thrust of his research is “green aviation.” He and his group are working on developing a more efficient helicopter that uses much less fuel.

In addition, Peters studies wind energy as a national renewable energy source, considering world energy needs, various alternative energy sources and the role that wind energy could play towards a sustainable energy program. He has presented his research at several conferences and taught a workshop on wind energy to area high school teachers.

Since the late 2000s, Peters has been the media “go-to guy” for commentary about the physical aspects of his favorite sport: baseball. An avid St. Louis Cardinals’ fan, Peters has commented on everything from the advantages of being left-handed in our national pastime to whether a runner might get an edge diving into a bag rather than running through it, to the importance of bat speed in hitting.

Since 2007, Peters, who chaired the department a total of 15 years, has been the department’s director of graduate studies, a position that provides him access to students (many of them part-time and from industry, just as he was years ago at McDonnell Douglas), research, industry consultation and classroom teaching. During his tenure, he has trained and mentored more than 70 doctoral students in his lab.

“It’s the perfect fit for me, and I love it,” he says. “One thing that I tell my students is that I won’t teach them anything that I didn’t actually use for somebody who paid me to do it. Hockey great Wayne Gretzky’s father told his son not to go where the puck is but where it’s going to be. That’s the neat thing about research. We can point people to where things are going to be 10 to 20 years from now, so we don’t teach for just the present, but for lifelong learning.”

Back to Engineering Momentum