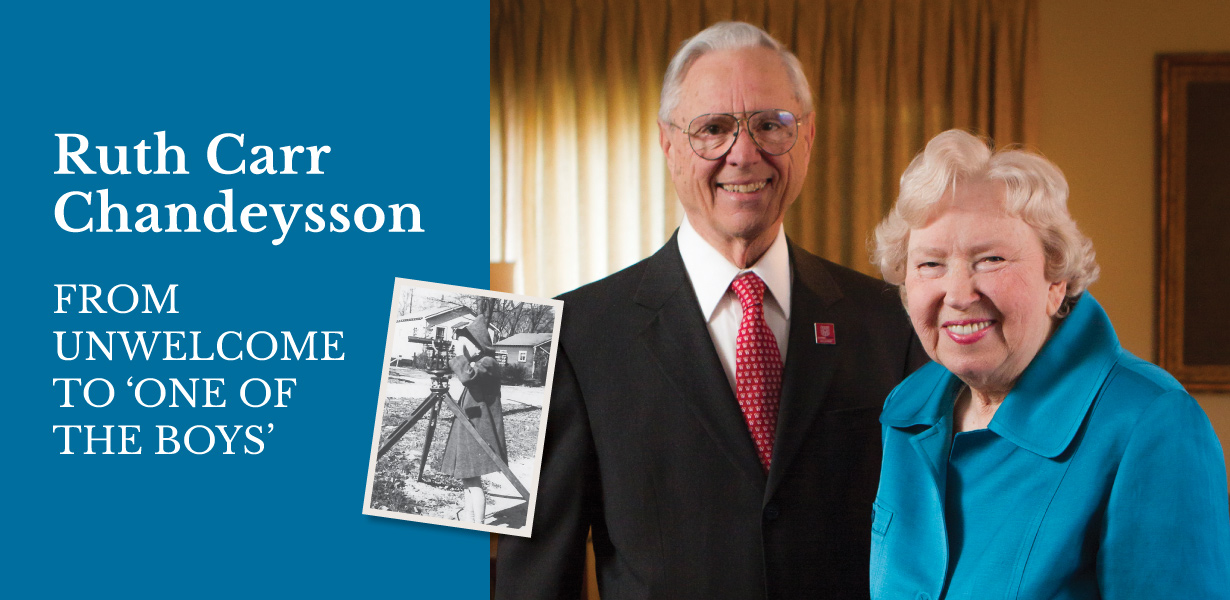

Ruth Carr Chandeysson

From unwelcome to ‘One of the boys’ What would it be like to be the only person like you in a class of 600 people?

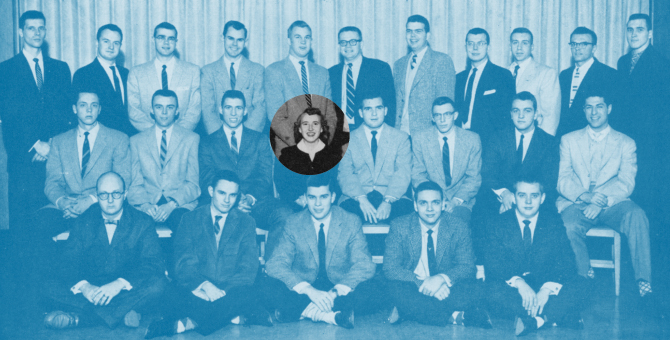

Ruth Carr Chandeysson knows. She was the only woman to graduate from Washington University in St. Louis, and in the state of Missouri, in 1957 with a bachelor’s degree in engineering.

“When I started, I was really looked down upon,” she recalls. “Everyone kept saying, ‘She’s not going to make it.’ It turned out that I did.”

Ruth, who earned a degree in civil engineering, is a role model for women in engineering at Washington University. While she was not the first woman to earn a bachelor’s degree in the school, she stayed the course for the full four years, when several women before her had dropped out.

Ruth vividly recalls one professor who particularly challenged her.

“He said, ‘This degree is not going to help you change diapers, and it’s not going to be able to make your husband happier,’” she says. “He also told me there was a bright boy out there who didn’t have a place at the school because I got his spot. I told him that if that boy were that bright, he’d have beaten me out for the spot. He stopped challenging me after that.”

In the mid-1950s, women pursuing engineering degrees were perceived as unfeminine, violating social norms or simply seeking a husband. Ruth came into WashU as none of those things and with nearly more experience in some areas than her professors.

A native of University City, Ruth was the daughter of a land surveyor. From a very young age, she tagged along with her father and helped him with his jobs, learning the craft along the way. By age 12, she was running her own survey crew and working for her father. She excelled in her math and science classes at University City High School so much that her guidance counselor sought out what requirements Ruth would need to be admitted into WashU’s engineering school. One of those requirements was a metal working shop, which up to that point, was only for males. The guidance counselor had to petition the school board to allow Ruth to take the course.

Although some WashU students and faculty created an unwelcome atmosphere for her, Ruth didn’t let it get her down.

“I always found it kind of a challenge,” she said. “I thought if I’m better than most of them, they’ll have to admit that I’m at least as good as they are.”

It didn’t take long for her classmates and professors to realize she could hold her own.

“I took surveying classes with the head of the department, and it was obvious that I knew enough about surveying that it didn’t bother anybody in my class that I was bright enough to do it,” she said. “After that, they all wanted to be with Ruthie.”

Ruth was elected Engineering Ball Queen as a sophomore and Military Ball Queen as a senior. She was a member of the Engineering Council as well. But, as with today’s students, she spent a lot of time studying — but not all of her time.

In her freshman English class, all but one of the other students ignored her. That student, Paul Chandeysson, was the only male student who would hold the door open for her after class. They began dating around Christmas time that year and have been married for 56 years. They now have three children and six grandchildren.

By the end of her education at WashU, Ruth had become “one of the boys,” her professor wrote in an article that appeared in the Missouri Engineer newsletter. She graduated in the top 10 of her class.

Paul Chandeysson, MD, earned bachelor’s degrees in mechanical and electrical engineering at WashU in 1958, a master’s in nuclear engineering from Stanford University in 1962, and a medical degree from George Washington University in 1976. He is the medical officer for the U.S. Food & Drug Administration and oversees the division that regulates medical devices such as pacemakers, artificial hearts and heart valves.

While Paul finished his bachelor’s degrees at WashU, Ruth worked in the stress analysis group at Emerson Electric on Little John missile system used by the U.S. Army in the 1950s and ‘60s. Her group designed and tested the jettisonable shoes on the bottom of the rocket.

A woman working as an engineer in the late 1950s was certainly rare, but Ruth’s expertise carried her far.

“It was pretty high-level aerospace engineering, and that requires a great deal of sophisticated engineering. She was up to that. She rocked ‘em and socked ‘em with what she could do,” Paul says.

While she loved her work, she ran into some discrimination in the corporate world.

“My supervisors at Emerson asked me to sign my name R.E. Carr,” she says. “A couple of times, people would call and ask for R.E. Carr, and when I got on the phone, they said they wanted to talk to R.E. Carr ‘the man.’ When I said I was R.E. Carr, they asked for a supervisor. My supervisor told them I did the work, so they would have to talk to me. Usually they decided I knew what I was talking about, so it worked out ok.”

After Paul graduated, the couple moved to El Paso, Texas, where he was in the Army for two years. Although she wasn’t working, her team from Emerson often came to El Paso for product testing, and they would ask for her help with the testing.

From there the couple moved to California while Paul earned a master’s degree, then on to Waco, Texas, where Paul worked for Rocketdyne for 10 years. At age 36, he started medical school at George Washington University, while Ruth was home raising their three young children.

“Paul always said, ‘You got the hardest job,’” she says.

Getting her education and working in the male-dominated engineering culture in the 1950s did create some soul searching, Ruth says.

“For a long time I had a feeling, ‘Am I more of an engineer than I am a woman?’” she says. “But I decided I could be both. I really enjoyed being an engineer and a mother and a wife.”

And that’s the same advice she offers to female engineering students: “Continue to be a woman,” she says. “If you treat people right, they’ll treat you right. It’s much better to do the best job you can and be as good of an engineer as you can and still be a nice, friendly person.”

Back to Engineering Momentum