Engineers develop novel hybrid nanomaterials to transform water

A team of engineers at Washington University in St. Louis has found a way to use graphene oxide sheets to transform dirty water into drinking water, and it could be a global game-changer

Graphene oxide has been hailed as a veritable wonder material; when incorporated into nanocellulose foam, the lab-created substance is light, strong and flexible, conducting heat and electricity quickly and efficiently.

Now, a team of engineers at Washington University in St. Louis has found a way to use graphene oxide sheets to transform dirty water into drinking water, and it could be a global game-changer.

“We hope that for countries where there is ample sunlight, such as India, you’ll be able to take some dirty water, evaporate it using our material, and collect fresh water,” said Srikanth Singamaneni, associate professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at the School of Engineering & Applied Science.

The new approach combines bacteria-produced cellulose and graphene oxide to form a bi-layered biofoam. A paper detailing the research is available online in Advanced Materials.

“The process is extremely simple,” Singamaneni said. “The beauty is that the nanoscale cellulose fiber network produced by bacteria has excellent ability move the water from the bulk to the evaporative surface while minimizing the heat coming down, and the entire thing is produced in one shot.

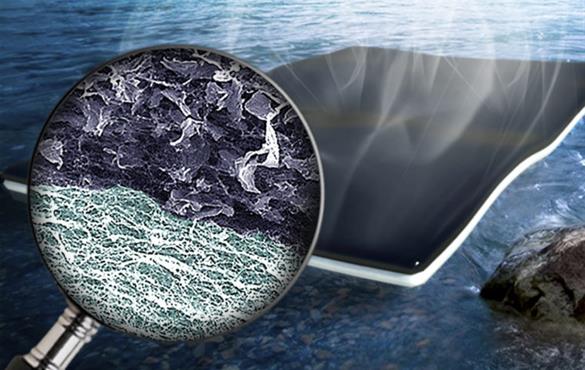

“The design of the material is novel here,” Singamaneni said. “You have a bi-layered structure with light-absorbing graphene oxide filled nanocellulose at the top and pristine nanocellulose at the bottom. When you suspend this entire thing on water, the water is actually able to reach the top surface where evaporation happens.

“Light radiates on top of it, and it converts into heat because of the graphene oxide — but the heat dissipation to the bulk water underneath is minimized by the pristine nanocellulose layer. You don’t want to waste the heat; you want to confine the heat to the top layer where the evaporation is actually happening.”

The cellulose at the bottom of the bi-layered biofoam acts as a sponge, drawing water up to the graphene oxide where rapid evaporation occurs. The resulting fresh water can easily be collected from the top of the sheet.

The process in which the bi-layered biofoam is actually formed is also novel. In the same way an oyster makes a pearl, the bacteria forms layers of nanocellulose fibers in which the graphene oxide flakes get embedded.

“While we are culturing the bacteria for the cellulose, we added the graphene oxide flakes into the medium itself,” said Qisheng Jiang, lead author of the paper and a graduate student in the Singamaneni lab.

“The graphene oxide becomes embedded as the bacteria produces the cellulose. At a certain point along the process, we stop, remove the medium with the graphene oxide and reintroduce fresh medium. That produces the next layer of our foam. The interface is very strong; mechanically, it is quite robust.”

The new biofoam is also extremely light and inexpensive to make, making it a viable tool for water purification and desalination.

“Cellulose can be produced on a massive scale,” Singamaneni said, “and graphene oxide is extremely cheap — people can produce tons, truly tons, of it. Both materials going into this are highly scalable. So one can imagine making huge sheets of the biofoam.”

“The properties of this foam material that we synthesized has characteristics that enhances solar energy harvesting. Thus, it is more effective in cleaning up water,” said Pratim Biswas, the Lucy and Stanley Lopata Professor and chair of the Department of Energy, Environmental & Chemical Engineering.

“The synthesis process also allows addition of other nanostructured materials to the foam that will increase the rate of destruction of the bacteria and other contaminants, and make it safe to drink. We will also explore other applications for these novel structures.”