‘Blink’ and you won’t miss amyloids

Tiny protein structures called amyloids are key to understanding certain devastating age-related diseases

Engineering team just found new way to see proteins that cause Alzheimer’s, other diseases

Tiny protein structures called amyloids are key to understanding certain devastating age-related diseases. Aggregates, or sticky clumped-up amyloids, form plaques in the brain, and are the main culprits in the progression of Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases.

Amyloids are so tiny that they can’t be visualized using conventional microscopic techniques. A team of engineers at Washington University in St. Louis has developed a new technique that uses temporary fluorescence, causing the amyloids to flash, or “blink,” and allowing researchers to better spot these problematic proteins.

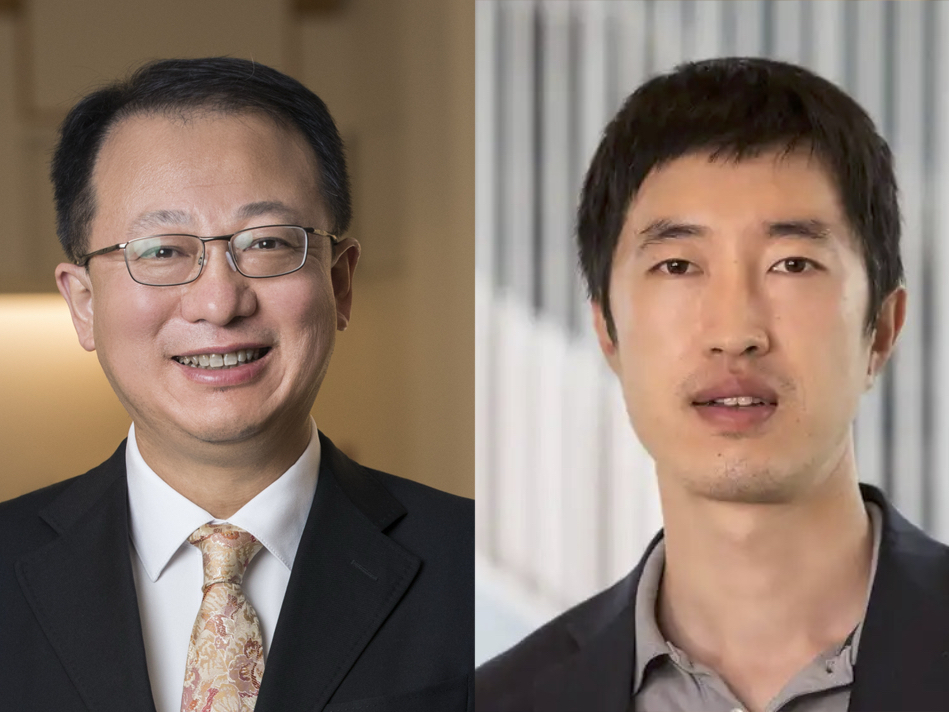

“It has been pretty difficult, finding a way to image them in a non-invasive way — not changing the way they come together — and also figuring out a way to image them long-term to see how they clump and form larger structures,” said Matthew Lew, assistant professor in the Preston M. Green Department of Electrical & Systems Engineering at the School of Engineering & Applied Science. “That was the focus of our research.”

Currently, scientists seeking to visualize amyloids use large amounts of a fluorescent material to coat the proteins in a test tube. When using a fluorescence microscope, the amyloids glow. However, it isn’t known how dyes that are permanently attached might alter the basic structure and behavior of the amyloid. It’s also difficult to discern the nanoscale structures at play using this bulk experimental technique.

Lew, whose research focus includes super-resolution microscopy and single-molecule imaging, worked with his former Washington University colleague Jan Bieschke, now an associate professor of brain science at University College in London, to develop the new technique that makes them blink. It’s called transient amyloid binding (TAB) imaging.

TAB uses a standard dye called thioflavin T, but instead of coating the amyloids, it temporarily sticks to them one at a time. The effect isn’t permanent, and the amyloids emits light until the dye detaches, yielding a distinctive blinking effect. The researchers were able to use a fluorescence microscope to observe and record the blinks. They then localized the position of each blinking thioflavin and reconstructed a super-resolved picture of the exact amyloid structure.

“The thioflavin T behaved like a group of fireflies, lighting up anytime they come into contact with the amyloid,” Bieschke said.

“What we saw were flashes of light over time,” Lew said. “On our computer screens, you’d see these individual spots blinking in sequence. We were then able to overlay all these dots together, giving us a complete look at the structure. If you didn’t separate them out, you’d see a blur.”

The team tested the TAB technique on a variety of amyloid structures and were able to reconstruct images for all of them, over an extended period of time and at various stages of aggregation. Their results were recently published in the journal ChemBioChem.

“There’s an intimate connection between seeing the proteins’ structure and learning how these proteins interact with neurons,” Lew said. “Ultimately, we need the imaging to understand all of the different shapes and structures that these proteins are building over time, and how that relates to the death of cells later on.”