Moon to engineer microbes to control heat production

New research is funded by the Office of Naval Research

Since the 18th century, thousands of women in Jeju, South Korea, have made a living diving in icy cold water for seafood and seaweed. Only recently did these women, known as Haenyeo, start wearing wetsuits designed to keep them warm. While researchers have studied some of the factors that may contribute to their tolerance of cold water for long periods of time, an engineer in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis thinks it might be a result of bacteria.

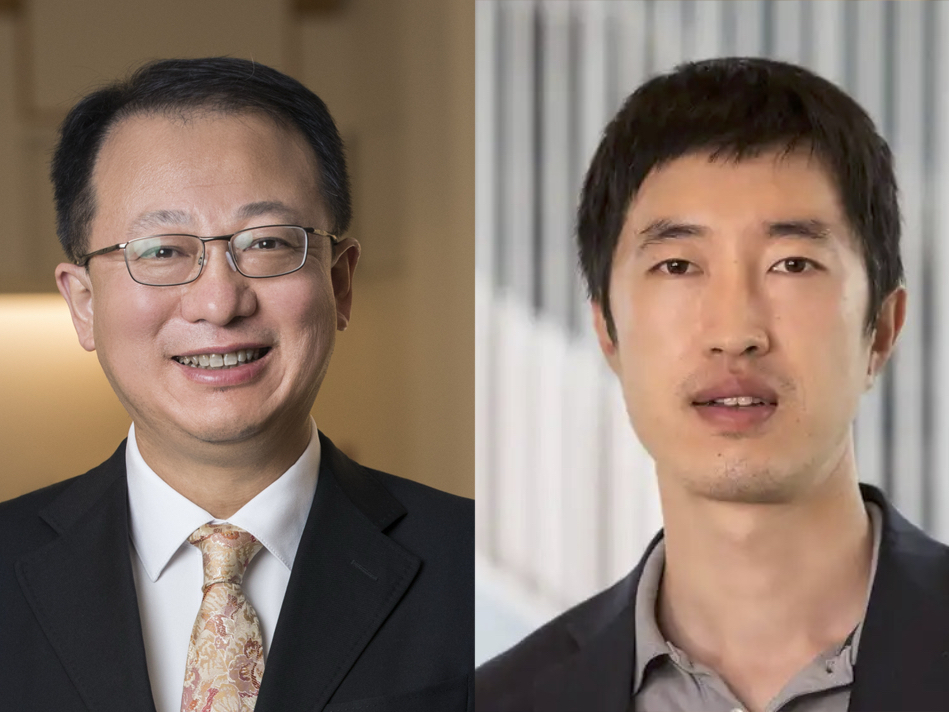

Tae Seok Moon, associate professor of energy, environmental & chemical engineering, has received a three-year, $501,246 grant from the Office of Naval Research to study how heat from the human microbiota may contribute to maintaining body temperature in cold environments.

“This is the craziest idea I’ve ever imagined,” said Moon, whose research involves developing genetic sensors for bacteria. “At the end of the day, I want to manipulate bacteria to help us maintain body temperature. The findings may help guide real-world applications, such as preventing hypothermia."

Moon will use his extensive expertise in synthetic biology and state-of-the-art technology to manipulate bacteria one gene at a time to understand which might be the key to producing heat by creating a microbial thermostat. By making the metabolism of bacteria inefficient, he can better understand how it produces heat. He will begin with a harmless form of E. coli bacteria as the model to understand the basic heat generation mechanism.

“The biggest challenge of the divers, both the women in Korea and divers in the U.S. military, is not staying warm during the dive, but once they are out of the water,” he said. “I want to determine how bacteria help to generate heat.”