Stretchy, bendy, flexible LEDs

They’re also cheaper, faster and fabricated with an inkjet printer

Sure, you could attach two screens with a hinge and call a cell phone “foldable,” but what if you could roll it up and put it in your wallet? Or stretch it around your wrist to wear it as a watch?

The next step in digital displays being developed at the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis could make that a reality.

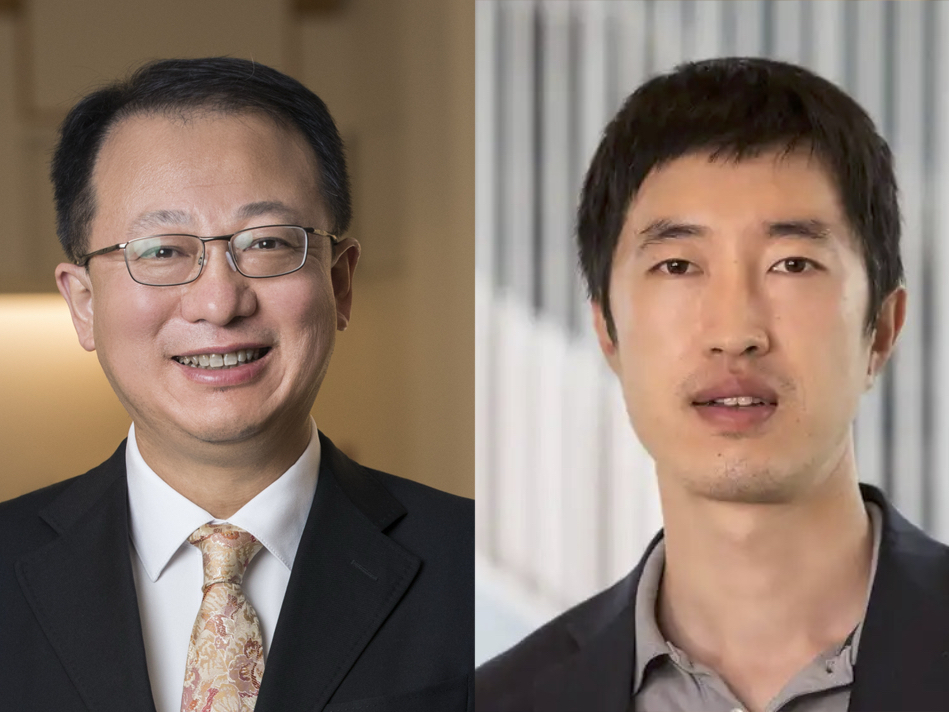

First, there were light-emitting diodes, or LEDs. Then, organic LEDs, or OLEDs. Now, researchers in the lab of Chuan Wang, assistant professor in the Preston M. Green Department of Electrical & Systems Engineering, have developed a new material that has the best of both technologies and a novel way to fabricate it — using an inkjet printer.

The research was published this month in the journal Advanced Materials.

Organic LEDs, made with organic small molecules or polymer materials, are cheap and flexible. “You can bend or stretch them — but they have relatively low performance and short lifetime,” Wang said. “Inorganic LEDs such as microLEDs are high performing, super bright and very reliable, but not flexible and very expensive.”

“What we have made is an organic-inorganic compound,” he said. “It has the best of both worlds.”

They used a particular type of crystalline material called an organometal halide perovskite — though with a novel twist. The traditional way to create a thin layer of perovskite, which is in liquid form, is to drip it onto a flat, spinning substrate, like a spin art toy, in a process known as spin coating. As the substrate spins, the liquid spreads out, eventually covering it in a thin layer.

From there, it can be recovered and made into perovskite LEDs, or PeLEDs.

Like spin art, however, a lot of material is wasted in that process — as the substrate spins at several thousand RPM, some of the dripping perovskite splatters and flies away, not sticking to the substrate.

“Because it comes in a liquid form,” Wang said, “we imagined we could use an inkjet printer” in place of spin coating.

Inkjet fabrication saves materials, as the perovskite can be deposited only where it’s needed, in a similar way to the precision with which letters and numbers are printed on a piece of paper; no splatter, less waste. The process is much faster as well, cutting fabrication time from more than five hours to less than 25 minutes.

Another benefit of using the inkjet printing method has the potential to reshape the future of electronics: perovskite can be printed onto a variety of unconventional substrates, including those that wouldn’t lend themselves to stability while spinning — materials such as rubber.

“Imagine having a device that starts out the size of a cell phone but can be stretched to the size of a tablet,” Wang said.

For a display to be flexible, however, printing stiff LEDs on rubber won’t do the trick. The LEDs themselves need to be flexible. Perovskite is not.

First author Junyi Zhao, a PhD candidate in Wang’s lab, was able to solve the problem by embedding the inorganic perovskite crystals into an organic, polymer matrix made of polymer binders. This made the perovskite and, by association, the PeLEDs, themselves, elastic and stretchable in nature.

The best of both worlds.

The process wasn’t exactly straightforward. It took long days — and a few nights — in the lab before getting it right. Wang and Zhao agreed that the biggest roadblock was making sure the different layers of material didn’t mix.

Because all parts of the PeLED were made from liquid — the perovskite layer as well as the two electrodes and a buffer layer — a major concern was keeping all of the layers from mixing.

LEDs are constructed in a sandwich-like configuration, with at least an emissive layer, an anode layer and a cathode layer. Additional layers such as electron and hole transporting layers may sometimes also be used. Zhao had to keep the perovskite layer safe from mixing with any of the others, the way running a highlighter over freshly written ink might smear it.

He needed to find a suitable polymer, one that could be inserted between the perovskite and the other layers, protecting it from them while not interfering too much with the PeLED’s performance.

“We found the best material and best thickness to balance performance and protection of the device,” Zhao said. After that, he went on to print the first stretchy PeLEDs.

These PeLEDs may be just the first step in an electronics revolution: Walls could provide lighting or even display the day’s newspaper. They can be used to make wearable devices, even smart wearables, like a pulse oximeter to measure blood oxygen.

Most excitingly, being able to print stretchy, flexible PeLEDs cheaply and quickly may lead to new technologies yet to be dreamed up.