By design: from waste to next-gen carbon fiber

A new chemically designed lignin leads to stronger, lighter carbon fiber and better recycled plastics

Research from Washington University in St. Louis may soon lead to lighter, stronger carbon fiber materials and stronger plastics with a gentler environmental impact. The main ingredient necessary for these improvements is lignin, a compound that is essential for most plants but considered a waste product by industry.

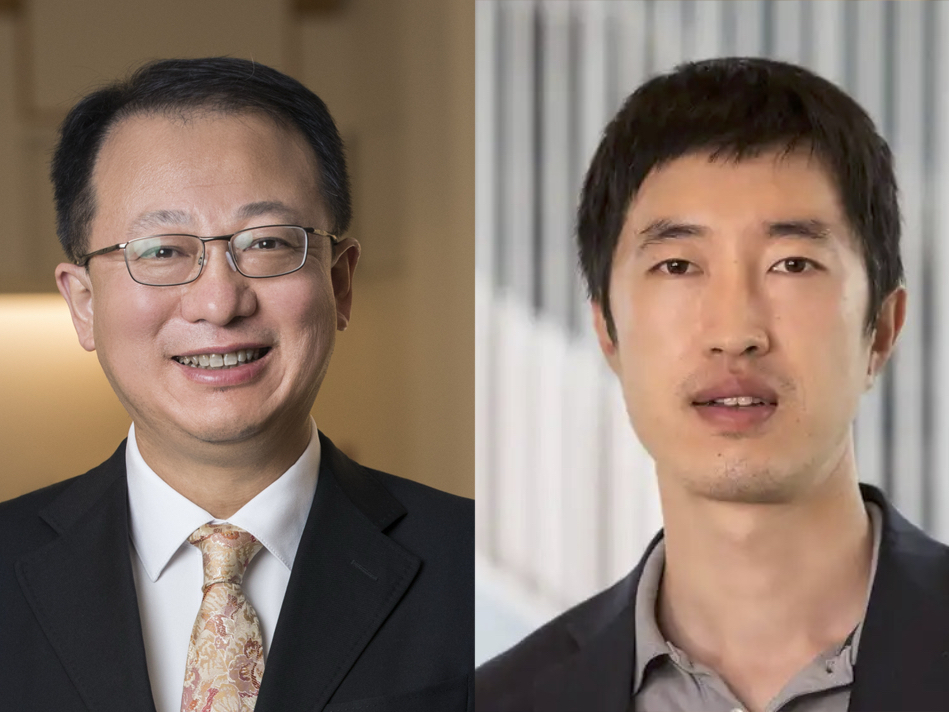

The key to opening up lignin’s potential was chemically altering some of its properties. High Molecular Weight Esterified Linkage Lignin (HiMWELL) was designed by the group of Joshua Yuan, professor and chair of the Department of Energy, Environmental & Chemical Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis’ McKelvey School of Engineering.

The research was published Aug. 11 in the journal Cell Press Matter.

Researchers knew that, combined with polyacrylonitrile (PAN), the newly designed HiMWELL lignin could become a precursor to a better carbon fiber and that it could enable the development of recyclable plastics with better properties, as well.

Already, carbon fiber is known for being a strong and stiff, yet light — and premium — material. It is used as structural reinforcement in everything from tennis rackets to airplanes, and carbon fiber frames reduce weight and improve safety in high-end vehicles. It has been incorporated anywhere possible in some of the fastest super and hypercars.

Yuan’s previous work identified three main roadblocks to incorporating lignin in the equation: neither lignin’s chemical structure nor its molecular weight is uniform, which makes it difficult to combine with other polymers. And it has a high number of OH groups, a reactive pairing of oxygen and hydrogen that attracts water — not ideal for building a rigid material like carbon fiber. These discoveries inspired Yuan and Jinghao Li, a senior scientist at Washington University, to redesign lignin structures.

By developing a technique to chemically alter these properties, Yuan said, “We’ve really created a type of lignin that is very unique.”

When combined with PAN, the HiMWELL-based carbon fiber had a record tensile strength and showed better mechanical properties than standard carbon fiber. When it was added to recyclable polymer blends, HiMWELL improved mechanical properties and also improved UV protection.

“Finally, we have a technological path for lignin to be used for carbon fibers,” Yuan said. And perhaps one day, “You’ll turn this waste into the shell of a car.”

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy and Bioenergy Technologies Office supported the work.

The research is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, grant # EE0008250