Engineered to serve

A woman in India prepares a meal using a traditional wood-burning cookstove in her home while her children are nearby. The photo is from Gautam Yadama’s book “Fires, Fuel, and the Fate of 3 Billion: Portraits of the Energy Impoverished” published by Oxford University Press. Yadama, PhD, is professor and director of international programs at The Brown School.

Michael Liu and Victoria Wang, both seniors, have been good friends since they met their freshman year. During the spring of that year, they pledged Alpha Phi Omega, a national, co-ed service fraternity with a large, active chapter at Washington University. The organization, founded on the principles of leadership, friendship and service, provides members with the opportunity to develop leadership skills as they volunteer on their campuses, in their communities and for their nation. Each member is required to do 15 hours of service each semester.

The WUSTL chapter cooks meals for families staying at the Ronald McDonald House, works in greenhouses and cleans up trash for Brightside St. Louis, plays with children at the St. Louis Crisis Nursery, directs spectators at Busch Stadium to recycle food and drink containers, and works on campus at Dance Marathon and Relay for Life, among many other opportunities.

"It's probably been one of the most valuable experiences I've had in college because it uses the passion for service to motivate you to think about how you are a leader and how you effect change in the community," says Wang, who is majoring in biomedical engineering. "Without this opportunity, I wouldn't have any of the subsequent opportunities I've had in college. The leadership courses and being able to spend time understanding how the organizations work and seeing how nonprofits work in St. Louis have been invaluable. In some ways, it's a responsibility we have as Wash U. students to understand what happens outside the bubble."

For both Liu and Wang, service is part of their very nature.

"My parents taught me that if I can't give back, I should try to give forward," says Liu, who is majoring in computer science with a minor in psychology. "Coming to Wash U. is a great opportunity for me to not only become better educated, but having this opportunity to give is a great way that I can help shape the future."

Liu and Wang are just two of the hundreds of students in the School of Engineering & Applied Science who devote at least a few hours a week from their already busy schedules to community service. From tutoring children in the community and their peers on campus, to walking dogs for Stray Rescue of St. Louis, to going to Africa to help a school for blind children, Engineering students think beyond their immediate needs in consideration of how to help others. Through these opportunities, they can apply the skills and experience they are learning through their coursework, as well as serve society — either locally or across the globe.

"Our students have the ability and want to do more than only engineering," says Melanie Osborn, assistant dean in Engineering Student Services. "The engineering is a great help, because they can not only go someplace and help someone, they can go there and repair the equipment, instruct others, and be involved in a deeper way. They have a lot of added value that they bring. Instead of just a pair of hands, they are the people who can figure out what everybody's pair of hands should do."

Osborn says students entering the School of Engineering & Applied Science are coming in with service experience from high school and they want to continue that through their college years.

Instilling a love for STEM

In high school, William Padovano was involved in a Lego Robotics program, which uses a sophisticated Lego set called Lego Mindstorms that includes the gears, sensors, motors and other parts needed to build moving robots and cars. Now a junior majoring in biomedical engineering, Padovano wanted to use that experience to share with others his love for STEM.

He teamed with his friend, David Kim, also a junior majoring in biomedical engineering, who had been volunteering at the St. Louis Juvenile Detention Center. In early February, the two started a Lego Robotics program at the detention center where the youth built and raced cars, based on Padovano's high school program. In fact, Padovano's Lego Robotics adviser from high school donated an old Lego Mindstorms for them to use.

"We didn't want to make it a traditional classroom with lectures and homework," Padovano says. "Our goal is to make science and engineering fun so they will learn a lot and not actually know that they are learning.

"One week, instead of an assigned car, we had a free build where they were asked to make a car that goes as fast as possible," Padovano says. "We gave them instructions and a model. One team independently came up with a better design and won the competition. It's really impressive how easily they grasped the concepts and surprising how excited they are."

Connie Shao, a senior in biomedical engineering, has been external vice president for Student Union since 2010 and co-founded the Journal Club for Undergraduates in Biological Engineering in 2011. A John B. Ervin Scholar, Shao has done research in the lab of Igor Efimov, PhD; at the School of Medicine; and in industry. On top of her academic course load and preparing for medical school next year, she volunteers with patients at St. Louis Children's Hospital; with Math Circle, which creates fun projects with math for local middle school students; and with Cadence with Care, in which volunteers play musical instruments for patients at the Siteman Cancer Center.

"Math Circle is something I care a lot about and is important to me because I grew up loving math," Shao says. "It's one of the things I found refuge in as a kid. What I really enjoy about Math Circle is working with middle school, high school and elementary kids to help them develop that passion for math."

Improving air quality and safety

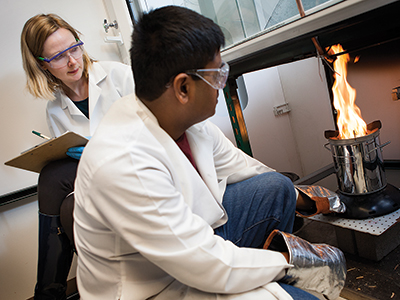

While Engineering students are involved in their own city, many also are drawn to global issues. Anna Leavey, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher, and Sameer Patel, a doctoral student, both work in the lab of Pratim Biswas, PhD, chair and the Lucy & Stanley Lopata Professor of Energy, Environmental & Chemical Engineering, measuring emissions from traditional and improved cookstoves relied upon by 3 billion people in developing countries worldwide, including India.

They are part of a larger university group working on a variety of aspects of cookstoves.

In these developing countries, many families in rural villages have no access to electricity, so the women cook meals on and heat their homes with a traditional indoor cookstove, a small, freestanding unit fueled by any materials they can find — wood, sticks, scavenged coal or dried animal dung. The rooms are small with little ventilation, so the smoke from the burning fuel and cooking food stays inside the home, where it is inhaled by everyone inside.

Each year, 2 million people worldwide die from cookstove-related illnesses, primarily women and children.

Leavey went with the team to rural Udiapur, India, in 2012 to measure the emissions from these traditional cookstoves.

"I'd read about it a lot, but you don't realize how harsh it is until you're actually standing there," Leavey says. "The air would fill with smoke. It was incredible — your eyes would water. And they did this two to three times a day, and often their children were with them.

"It also creates environmental issues with the depletion of biomass, as well as security issues: when women have to walk further from home to find fuel, the risk of violence against them increases when they leave their villages," Leavey says.

In addition to studying the composition and effects of the emissions from the traditional cookstoves, the team is studying the use of improved cookstoves that have been distributed by nongovernmental organizations across India and other countries. One of the most common improved cookstoves has an integrated fan, but it requires electricity, so many stop using it.

Engineers Without Borders addresses many needs

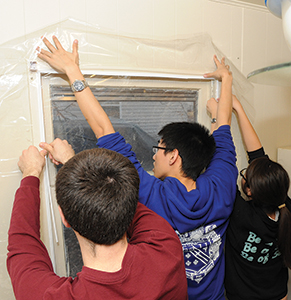

Through the Washington University chapter of Engineers Without Borders (EWB), a national organization that supports community development projects worldwide, Engineering undergraduate students are involved in a variety of local and international projects.

Locally, a group of EWB members is working with a church community and another group in the Hyde Park neighborhood of north St. Louis to design a bioretention basin in an empty lot. The basin is a type of rain garden used as a filtration system to reduce rainwater runoff into sewers, says team leader Lucy Cheadle, a junior majoring in chemical engineering with a minor in environmental engineering and energy engineering.

The Hyde Park project team consists of WUSTL undergraduates as well as students in the UMSL/Wash U. Joint Engineering Program, which brings strength in all areas of engineering, as well as a group focused on local projects, Cheadle says.

"I think it's important to stay local," she says. "St. Louis has a lot of nice areas, but it also has a lot of areas that need help."

Another EWB team is developing medical devices that could be used in developing countries. The team, headed by sophomore Huy Lam, who is majoring in biomedical engineering, has four teams of students this year working on projects including transdermal patches that would deliver antibiotics or zinc, a device that would help keep vaccinations from freezing, and a device that would be a portable tool to assist dentists avoid hitting nerve endings in dental surgery.

"From day one, we go to the World Health Organization to see what the world needs," he says. "In a sense, this design team is a simulation of what entrepreneurship will be like. Our team is very problem-oriented: many people on the team are not interested in making a for-profit company."

Carolyn Arden, a sophomore majoring in systems science and engineering and Spanish, heads another team under the EWB umbrella, the Washington University Guatemala Initiative (WU-GI). Last year, Arden worked with BJC HealthCare staff learning how to repair an older model ventilator in use at Roosevelt Hospital in Guatemala City, Guatemala. She visited the hospital in the summer of 2013 with the School of Medicine's Global Health Scholars to meet with doctors, surgeons, medical residents and hospital staff. While there, she "caught the bug."

"I said to myself, "I can't just leave and forget about this,'" she says. "This was not a project that we finish and forget about, because then, how can we ensure our impact is sustainable?"

When she returned from the trip, she started WU-GI, which has about 15 student members who are working with BJC staff to learn how to repair medical equipment used by Roosevelt Hospital so they can repair it on service trips. The team is learning to repair ventilators, patient monitor displays and infant warmers, as well as building ECG simulators for the hospital to use in its emergency room and shock room in preparation for a trip this July.

"When I was in Guatemala, I took inventory of all the broken equipment, what needed to be repaired and things we could work on," she says. "I'm also working to translate repair manuals from English into Spanish, so if some of their equipment is broken, they can read how to fix it."

Arden says WU-GI has become a big part of her life. "Being down there changed my perspective," she says. "I just felt really empowered to do something. I could have left and said, "That was a great experience,' and put it my resume, but for me, it turned into something more. Here at Wash U. I'm given the tools and am fortunate enough to have the experience and the education to make a difference and impact, and I felt responsible to make something out of that experience and to continue it."

The other international travel arm of Engineers Without Borders is a team's work with the Mekele Blind School in Ethiopia. A group of WUSTL EWB students has made the trip to Ethiopia for several years. Most recently, the team spent two weeks at the school, upgrading the electrical system to improve the cooking methods and adding outdoor lighting for safety and security.

Maeve Woeltje, a junior majoring in biomedical engineering and one of the co-leaders of the trip, said the residential school, which serves about 100 students, was using just two stoves to cook 200 pieces of injera bread every day because they did not have enough power to operate a third stove. In addition, they were unable to use two additional cooking stoves for other foods because they did not have enough electricity for them, so they were using wood-burning stoves indoors, creating unhealthy air quality. In addition to installing new circuit breakers, the team made plans for a new electric meter to be installed that will provide enough power for all of the electric cooking stoves.

This was Woeltje's first trip to Ethiopia.

"I have been involved with EWB for two years, so I was invested in the community," she says. "It was a good way to learn applicable things about engineering and implement them and also travel and explore a new culture."

Back to Engineering Momentum