Telescope-inspired microscope sees molecules in 6D

Details of this new system were published Dec. 5 in the journal Nature Photonics

A new technology, inspired in part by the design of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), uses mirror segments to sort and collect light on the microscopic scale, and capture images of molecules with a new level of resolution: position and orientation, each in three dimensions.

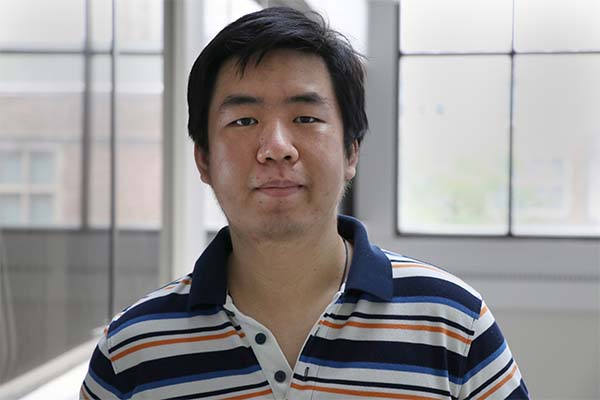

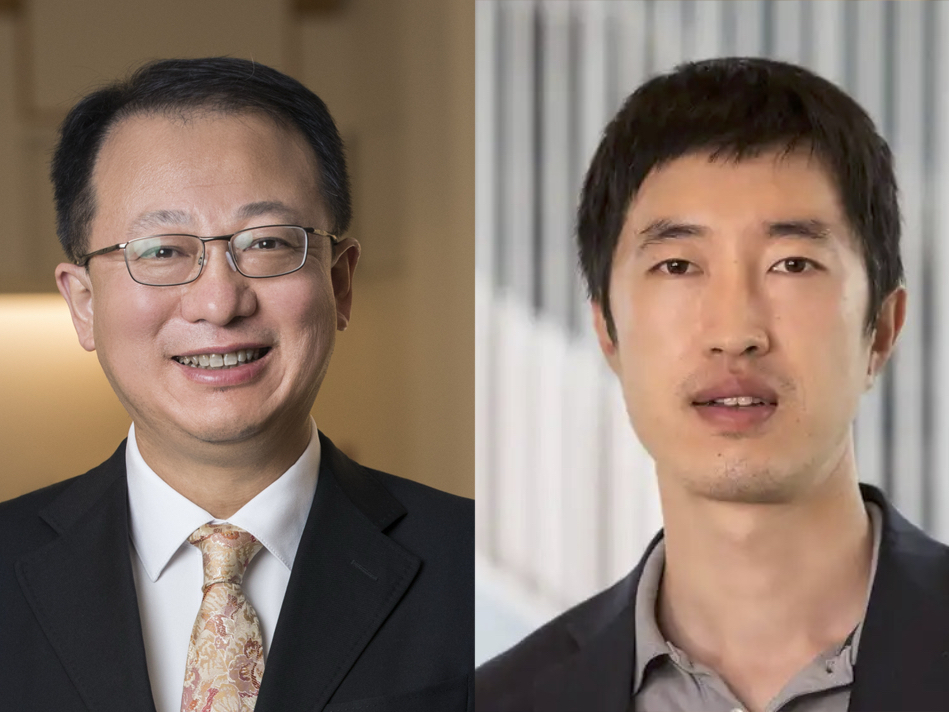

Details of this new system, developed by Oumeng Zhang, a recent PhD graduate from the lab of Matthew Lew, associate professor of electrical and systems engineering at the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis, were published December 5, 2022 in the journal Nature Photonics. Michael Vahey, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, also collaborated on this research.

Like the space telescope, the radially and azimuthally polarized multi-view reflector (raMVR) microscope depends on gathering as much light as possible. But instead of using that light to see things far away, it uses it to discern different features of tiny, fluorescent molecules attached to proteins and cell membranes.

“The setup is partially inspired by telescopes,” Zhang said. “It’s a very similar setup. Instead of the familiar honeycomb shape of the JWST, we use pyramid-shaped mirrors.”

Currently, microscopes in this domain face challenges creating biological images. For one thing, such small amounts of light given off by the fluorescent molecules are sensitive to the slightest aberrations — including the murky environment inside a cell. Because of this, precise imaging relies more heavily on computer processing to sort out orientation after an image has been captured.

“Think of creating a color picture when all you have are gray-scale camera sensors,” Lew said. “You could try to recreate the color using a computational tool, or you can directly measure it using a color sensor, which uses various absorbing color filters on top of different pixels to detect colors.”

In a similar way, standard microscopes simply do not detect how molecules are oriented. The raMVR microscope uses polarization optics called waveplates along with its pyramid-shaped mirrors to separate light into eight channels, each of which represents a different piece of the molecule’s position and orientation.

Notably, the raMVR microscope is not a small technology. But smaller isn’t always better.

“At the cutting edge of engineering physics, we often have to make tradeoffs to make our instruments compact,” Lew said. “Here, we decided to take a different tack: How could we use every precious bit of light to make the most precise measurement possible? It’s absolutely fun to think differently about the architecture of a microscope, and here, we think the newfound 6D imaging performance will enable new scientific discoveries in the near future.”

This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R21AI163985); the National Science Foundation (ECCS-1653777); and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (R35GM124858)